Dedekind cut

In mathematics, a Dedekind cut, named after Richard Dedekind, is a partition of the rational numbers into two non-empty parts A and B, such that all elements of A are less than all elements of B, and A contains no greatest element.

If B has a smallest element among the rationals, the cut corresponds to that rational. Otherwise, that cut defines a unique irrational number which, loosely speaking, fills the "gap" between A and B. In other words, A contains every rational number less than the cut, and B contains every rational number greater than the cut. An irrational cut is equated to an irrational number which is in neither set. Every real number, rational or not, is equated to one and only one cut of rationals.

Whenever, then, we have to do with a cut produced by no rational number, we create a new irrational number, which we regard as completely defined by this cut ... . From now on, therefore, to every definite cut there corresponds a definite rational or irrational number ....—Richard Dedekind, Continuity and Irrational Numbers, Section IV

More generally, a Dedekind cut is a partition of a totally ordered set into two non-empty parts (A and B), such that A is closed downwards (meaning that for all a in A, x ≤ a implies that x is in A as well) and B is closed upwards, and A contains no greatest element. See also completeness (order theory).

In particular, as discussed below, Dedekind cuts among the real numbers may be considered defined as cuts among the rationals. It turns out that every cut of reals is identical to the cut produced by a specific real number (which can be identified as the smallest element of the B set). In other words, the number line where every real number is defined as a Dedekind cut of rationals is a complete continuum without any further gaps.

Dedekind used the German word Schnitt (cut) in a visual sense rooted in Euclidean geometry. When two straight lines cross, one is said to cut the other. Dedekind's construction of the number line ensures that two crossing lines always have one point in common because each of them defines a Dedekind cut on the other.

Contents |

Representations

It is more symmetrical to use the (A,B) notation for Dedekind cuts, but each of A and B does determine the other. It can be a simplification, in terms of notation if nothing more, to concentrate on one 'half' — say, the lower one — and call any downward closed set A without greatest element a "Dedekind cut".

If the ordered set S is complete, then, for every Dedekind cut (A, B) of S, the set B must have a minimal element b, hence we must have that A is the interval ( −∞, b), and B the interval [b, +∞). In this case, we say that b is represented by the cut (A,B).

The important purpose of the Dedekind cut is to work with number sets that are not complete. The cut itself can represent a number not in the original collection of numbers (most often rational numbers). The cut can represent a number b, even though the numbers contained in the two sets A and B do not actually include the number b that their cut represents.

For example if A and B only contain rational numbers, they can still be cut at √2 by putting every negative rational number in A, along with every non-negative number whose square is less than 2; similarly B would contain every positive rational number whose square is greater than or equal to 2. Even though there is no rational value for √2, if the rational numbers are partitioned into A and B this way, the partition itself represents an irrational number.

Ordering of cuts

Regard one Dedekind cut (A, B) as less than another Dedekind cut (C, D) if A is a proper subset of C. Equivalently, if D is a proper subset of B, the cut (A, B) is again less than (C, D). In this way, set inclusion can be used to represent the ordering of numbers, and all other relations (greater than, less than or equal to, equal to, and so on) can be similarly created from set relations.

The set of all Dedekind cuts is itself a linearly ordered set (of sets). Moreover, the set of Dedekind cuts has the least-upper-bound property, i.e., every nonempty subset of it that has any upper bound has a least upper bound. Thus, constructing the set of Dedekind cuts serves the purpose of embedding the original ordered set S, which might not have had the least-upper-bound property, within a (usually larger) linearly ordered set that does have this useful property.

Construction of the real numbers

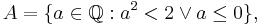

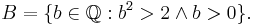

A typical Dedekind cut of the rational numbers is given by

This cut represents the irrational number √2 in Dedekind's construction. To truly establish this, one must show that this really is a cut and that it is the square root of two. However, neither claim is immediate. Showing that it is a cut requires showing that for any positive rational  with

with  , there is a rational

, there is a rational  with

with  and

and  The choice

The choice  works. Then we have a cut and it has a square no larger than 2, but to show equality requires showing that if

works. Then we have a cut and it has a square no larger than 2, but to show equality requires showing that if  is any rational number less than 2, then there is positive

is any rational number less than 2, then there is positive  in

in  with

with  .

.

Note that the equality b2 = 2 cannot hold since √2 is not rational.

Generalizations

A construction similar to Dedekind cuts is used for the construction of surreal numbers.

Partially ordered sets

More generally, if S is a partially ordered set, a completion of S means a complete lattice L with an order-embedding of S into L. The notion of complete lattice generalizes the least-upper-bound property of the reals.

One completion of S is the set of its downwardly closed subsets, ordered by inclusion. A related completion that preserves all existing sups and infs of S is obtained by the following construction: For each subset A of S, let Au denote the set of upper bounds of A, and let Al denote the set of lower bounds of A. (These operators form a Galois connection.) Then the Dedekind–MacNeille completion of S consists of all subsets A for which (Au)l = A; it is ordered by inclusion. The Dedekind-MacNeille completion is the smallest complete lattice with S embedded in it.

Allusions

In his chapter on Henri Bergson, the author C.E.M. Joad employed imagery that was similar to Dedekind's concept of the cut. Joad was trying to explain how Bergson saw the mind as an instrument that projected permanent objects onto the experience of constant change. "The intellect, then, is a purely practical faculty, which has evolved for the purposes of action. What it does is to take the ceaseless, living flow of which the universe is composed and to make cuts across it, inserting artificial stops or gaps in what is really a continuous and indivisible process. The effect of these stops or gaps is to produce the impression of a world of apparently solid objects. These have no existence as separate objects in reality; they are, as it were, the design or pattern which our intellects have impressed on reality to serve our purposes."[1] This is reminiscent of Dedekind's creation of a new irrational number at every gap in the continuous number line at which there is no existing real number.

See also

Notes

- ^ Great Philosophies of the World, C.E.M. Joad, Ch. VI, "The Philosophy of Change," 1930:Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, Inc.

References

- Dedekind, Richard, Essays on the Theory of Numbers, "Continuity and Irrational Numbers," Dover: New York, ISBN 0-486-21010-3. Also available at Project Gutenberg.